The Psychology behind Design: How can we shape the Student Precinct for healthy minds?

With more people living in cities and suburbs than ever before, neuroscientists and psychologists have turned their focus to how our built environments can affect our mood and well-being.

Researchers have found plenty of evidence that our interactions and even our vicinity to buildings and cities can have a significant impact on our physiology, with specialised cells in the hippocampal region of our brains being attuned to the geometry and arrangement of the spaces we inhabit1. This has led to an exciting new area of research and design commonly referred to as ‘neuro-architecture’.

Thanks to psychological studies, we now have a much better idea of the kinds of urban environments people find stimulating, welcoming and safe. These findings have been confirmed by the New Student Precinct's own co-creation research, which will inform the design of the NSP to support the health and wellbeing of our diverse student community. So how can the design of the New Student Precinct support the health and wellbeing of our diverse student cohort?

Visual complexity and variation of space

A consistent finding of the research shows that people are strongly affected by building facades2. The more complex and interesting the façade, the greater the positive effects on a subject’s physiology. Simple and monotonous facades prompt negative physiological responses. A 2013 virtual reality experiment in Iceland subjected participants to various residential street scenes3. This study found the scenes with greater architectural variation were the most mentally engaging.

Illustrative rendering of the New Student Precinct site showing some of the variation in building design, both existing and proposed for construction as part of the Project.

The Precinct site features period buildings from 1850 to 2000 and ranging in architectural style from classical to brutalist. Carefully considering the creative reuse of these buildings in a way that preserves their architectural character while ensuring they add value to the modern student experience will create a dynamic and stimulating environment across the Precinct. The unique Parkville Campus character of laneways and courtyards will also be retained and emphasised in the design, creating visually appealing and emotionally engaging spaces of various style, size, feel and function.

The importance of social interaction

A lack of social bonding and cohesion in communities has been found to significantly contribute to an individual’s risk of developing mental illnesses such as depression and chronic anxiety4. Research at the University of Heidelberg has shown that urban living can change brain biology, reducing grey-matter in the brain similar to changes attributed to early-life stressful experiences5. The meaningful social interactions crucial to maintaining mental health and wellbeing are difficult to find in urban communities with authorities recognising social isolation as a major risk factor in community health6.

The outdoor amphitheatre can be used for student-led activations and events, or a place for students to gather and socialise, day or night.

One way to increase social interaction is to create opportunities for individuals to ‘collide’ within a space. Thinking about how we can bring students together through creative space design will ensure the Precinct fosters social interaction and provide openings for students to develop meaningful relationships and support networks. Coupled with a student-led program of activations and events in which students can collaborate on creative and intellectually stimulating projects, the Precinct aims to support the mental health and wellbeing of its students.

Spaces that are easy to navigate

A sure-fire way to provoke feelings of anger and frustration is to design spaces that create a sense of being lost or disoriented. In the simplest of terms, people need an awareness of how the things around them relate spatially to develop a sense of direction7. However, this spatial-sensitivity is also required to foster connection and belonging to a place8.

The Student Precinct will develop a series of ‘arrival landscapes’, leading into courts and laneways that penetrate into and through buildings, creating a seamless pedestrian flow that draws visitors to the centre of the precinct, immediately orientating individuals with the surrounding buildings. Lowering the ground plane of the site will reveal the original façade of the buildings, allowing ground levels to be opened and reducing the byzantine series of stairways and levels that currently exist across the site.

An illustrative masterplan of the Precinct site showing the layout of buildings and landscapes. The grey areas show how the ground-level of buildings can be opened up to create a cohesive and welcoming pedestrian flow throughout the site.

Despite the obstacles urban design often put in the way, people are remarkably good and forcing their environments to work for them. A physical manifestation of this are ‘desire lines’ forged across parks and plazas and mapping people’s preferred path through a space9.

The Precinct has conceived a series of pathways, laneways and shortcuts across landscapes to provide multiple thoroughfares when moving around and reaching desired destinations with minimal fuss. In doing so, the project also ensures the Precinct is accessible to all students and visitors. A big part of this work has been the design of a built-in ‘desire line’, linking the Swanston Street tram stop to Monash Road. This informal pathway will make the centre of the precinct more visible as an entry way to the Parkville campus, allowing students to participate in activities occurring at the centre of the Precinct, or bypass major events held within the amphitheatre.

Green space and a connection to nature

Designers and psychologists are increasingly understanding the importance of nature in mitigating the negative effects our cities can have on our health and wellbeing. Access to nature in the form of green spaces that create a respite from the urban environment can have a significant impact on our ability to recover faster from stress-related health problems10.

The Precinct will be defined by a cohesive landscape and numerous rooftop and indoor gardens designed to connect students with nature and support diverse microclimates and ecologies; reduce heat; and provide shade and shelter. Wherever possible, the Precinct will incorporate plants and greenery to ensure maximum tree canopy coverage.

Illustrative image of the new Arts and Cultural Building showing early concepts for greening and roof top gardens.

Three main ‘arrival landscapes’ will be developed to provide students with places to occupy, activate and pause before entering the central Precinct landscape. Each of these ‘arrival landscapes’ will be designed to provide their own distinctive experiences and amenities, opening views and vistas into the Precincts centre.

Combined, this variety of landscapes and green-spaces will provide students with an escape from daily urban and university life, improving their ability to recover from the mental fatigue and stress synonymous with the modern student experience11.

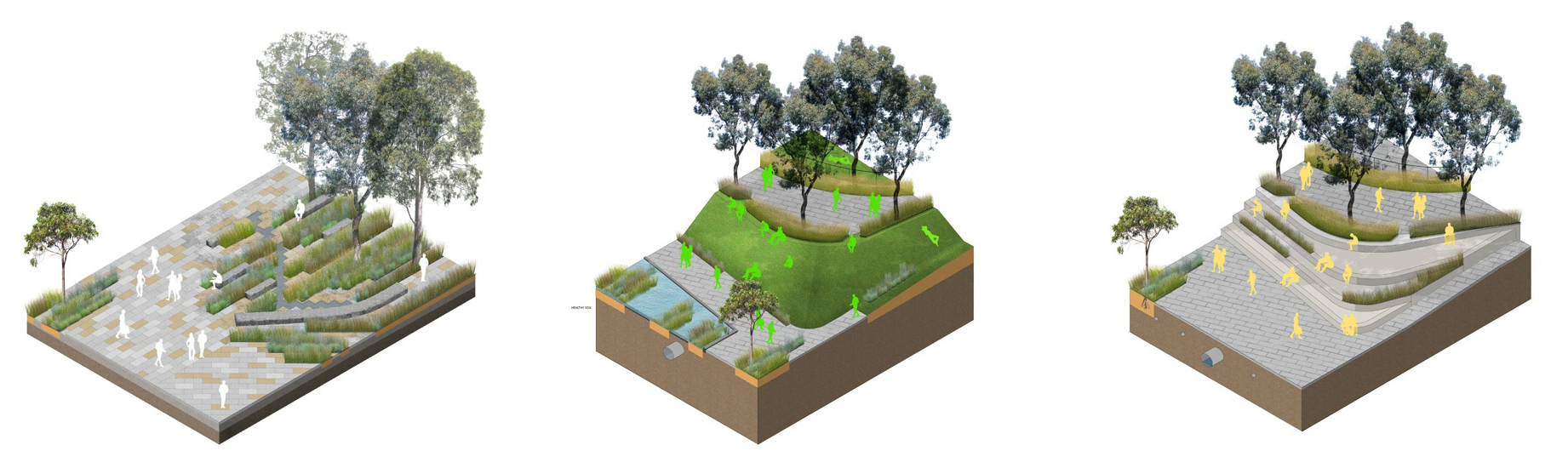

Landscape diagrams exploring options for maximising greening of the Precinct

References

- Grieves, R.M. & Jeffery, K.J., 2016. The representation of space in the brain. Behavioural Processes, Volume 135, pp. 113 - 131.

- Ellard, C. & Montgomery, C., 2013. Testing, Testing! A Psychological Study On City Spaces And How They Affect Our Bodies And Minds. BMW Guggenheim Lab.

- Lindal, P.J. & Hartig, T., 2013. Architectural variation, building height, and the restorative quality of urban residential landscapes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, Volume 33, pp.26 - 36.

- Newbury, J. Arseneault, L., Caspi, A., Moffittm T.E., Odgers, C.L. & Fisher, H.L., 2016. Why Are Children in Urban Neighborhoods at Increased Risk for Psychotic Symptoms? Findings From a UK Longitudinal Cohort Study. Schitzophrenia Bulletin, Volume 42(6), pp. 1372 - 1383.

- Haddad, L., Schafer, A., Streit, F., Lederbogen, F., Grimm, O., Wust, S., Deuschle, M., Kirsch, P., Tost, H. & Meyer-Lindenberg, A., 2014. Brain Structure Correlates of Urban Upbringing, an Environmental Risk Factor for Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 41(1), pp. 115 - 122.

- Kelly, J.F., 2012. Social Cities. GRATTAN Institute.

- Jeffrey, K.J., 2017. Spatial reference frames and the sense of direction. Anthologies, Conscious Cities: Bridging Neuroscience, Architecture , and Technology.

- Jeffrey, K.J., 2017. A Map to Attach Memories To. Losing Myself [Audio Recording].

- Smith, N. & Walters, P., 2017. Desire lines and defensive architecture in modern urban environments. Urban Studies, Volume 55(13), pp. 2980 - 2995.

- Li, D. & Sullivan, W.C., 2015. Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 148, pp. 149 - 158.

- Andrews, B. & Wilding, J.M., 2010. The relation of depression and anxiety to life-stress and achievement in students. British Journal of Psychology, Volume 95(4), pp. 509 - 521.