Integrated into the structural columns of Building 189, the Identity Bricks serve as a creative recognition of this site as an Indigenous place with a continuing and diverse Indigenous presence.

About the Identity Bricks

The Identity Bricks Project invited Indigenous students, staff and alumni to share and embed their cultural stories and journeys in a permanent installation on the Parkville campus.

The bricks symbolise reciprocity and mutual exchange related to working on Wurundjeri Country. Through this exchange, participants acknowledge the gifts they have received from Wurundjeri Country and its custodians, and gift something of their story, Country or community in return.

The project is a culmination of the combined efforts of the Student Precinct Project team, Murrup Barak Melbourne Institute of Indigenous Development, Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development and the wider Indigenous community at the University of Melbourne.

Identity Bricks Gallery

Please click on the images below to learn more about each identity brick and the cultural stories behind them.

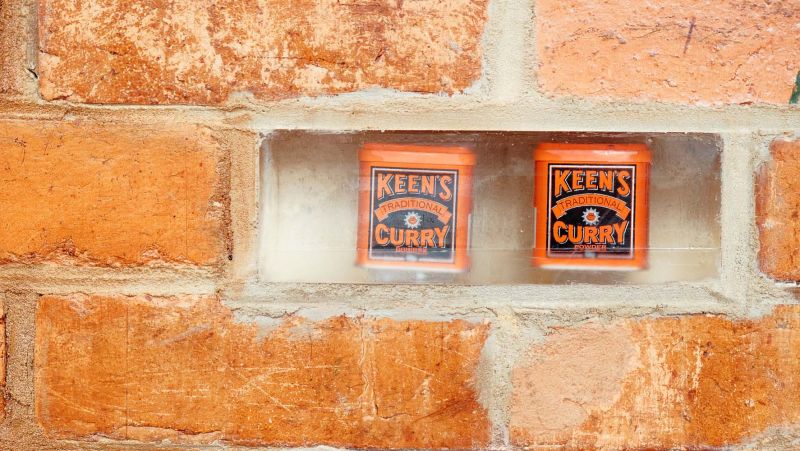

Keens Curry Tins

For the Community. Despite settler colonialism, we find ways to connect and relate. Though contemporary, it is symbols like Keen’s Curry that continue to provide a sense of community, connection, and belonging – a shared experience.

— Anonymous

Clapping Sticks

‘My identity as an Aboriginal man comes not purely from my ancestry but rather embracing and researching my culture and using the gifts given to me by Baiame (the Creator) to further my family and those around me. These Bilma (clap sticks) are cut from my Country with input from my mother and father.’

— Jon Watling, Wiradjuri

Sandalwood and Earth

‘I live and work on the lands of the Kulin nation but I have my country with me. Sandalwood from Badimia country and a piece of Warrdagga, our spiritual home.’

— Darren Clinch, Badimia Yamatji

Honer Blues Harmonica

‘This harmonica was used in the writing of one of my most significant and personal songs, ‘Arfa.’ The song is a conversation with my ancestors, in which I make it known my intention to continue to honour them and our culture.’

— James Howard, Jaadwa

Sculpted Turtle

‘The way to speak back to that tradition of colonial statues and memorials is to make our own.’

— Marcia Langton, Yiman and Bidjara

Painted Stethoscope

‘My identity as a Palawa man has been a big journey for me. Growing up, being pale-skinned and dealing with misconceptions and misinformation about who Palawa people are, it was a battle not to internalise some of the attitudes that I came up against. I have always known who I am despite not growing up surrounded by my culture in lutruwita, but it can be hard to be that person in the eyes of the world sometimes.

Through my studies to become a veterinarian, I had the opportunity to be a part of a volunteer vet program in remote communities in Arnhem Land. Through this I grew new connections to the animals, the land and the people, some of whom I’ve come to know as family. These experiences and the generosity of Bininj, Maung and Yolŋu mob have given me the opportunity to explore my own cultural identity more and build the confidence that I lacked growing up. I’ve furthered these experiences by undertaking a PhD studying One Health in remote communities.

My object is a stethoscope. There were a lot of natural objects I identify with as a Palawa man so it was initially difficult to choose, but my connection to culture and identity through my profession was something I kept coming back to. I’ve painted the stethoscope with symbols relating to my journey: my home of lutruwita, some of the country up north, dogs, parasites and symbols for health and healing.

Through serving communities, I’ve come to know them and myself better.’

— Cam Raw, Palawa

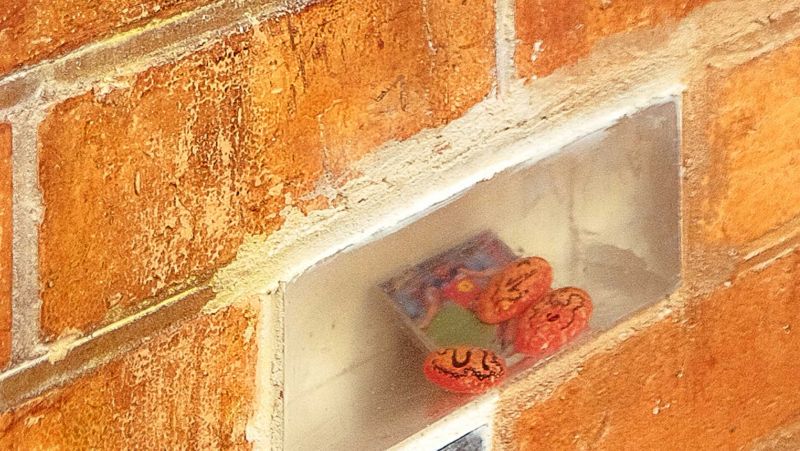

Painted Stone and AFL Card

‘I wanted to choose objects that reflect both sides of my family but also reflect the way I interpret my Indigenous culture. The 3 stones are from my dad's side (my uncle Mark Egan) and reflect how I associate art as a physical manifestation to my culture. The football card is of my uncle Chris Johnson (mum's side) and reflects how I associate my Indigenous identity to football and have always used it to express my culture.’

— Yemurraki Egan, Yorta Yorta, Wemba Wemba and Gunditjamara

Thick Bark

‘I chose a piece of bark from an old tree as my Identity Bricks object. I chose this because I feel a significant spiritual presence associated with old native trees. I have always felt a connection to country through trees, even before I knew I was Aboriginal. I grew up not knowing about my Indigeneity and only found out when I was 15 years old. Since learning of this, I've been on a journey of reclamation of my identity and culture. It's been a big learning-curve but I believe the spirits of my ancestors have been watching over me and are proud of how far I've come.

I can especially feel their presence when I place my hand on trees that have stood in the environment for a long time. I think it's amazing how old some of our native trees are and like to imagine what they've seen.

It can be difficult to connect to country when you live in a major city away from home but I've found that this is one of the best ways for me.’

— Brittney Andrews, Kaniyang, Noongar

Torres Strait Islands Flag and Dugong

‘Dugongs are important to Torres Strait Islanders. This dugong represents the well known creation story Gelam - A boy who turned into a Dugong travelling from Moa and settling at Mer and creating the Islands of Waier and Dauar.’

— Matthew Starr, Meriam Mir/Kala Lagaw

Yothu Yindi : The Tribal Voice Album Cassette

‘For me I feel like one of the most influential songs from the album is Treaty. So it’s just something that you would hear at current events now, and all the way back in the early 90s and 80s when the song came out.’

— Kirsten Hausia, Badimaya Yamatji

Woven Earrings

‘Weaving feels so universal. I can connect with other Blak fullas through weaving even if they’re not from the same mob and that feels really important when living off Country. Weaving also creates objects that I use as body adornments, so I can wear my identity.’

— Kayla Clinch, Badimaya Yamatji

Manna Gum Leaves

‘The importance of the trees to the local Wurundjeri People, I have worked very closely with many locals, this Country has been an inspiration, a teacher and a healer, and on Billibellary’s Walk, and these trees form part of that.’

— Craig Hunter Torrens, Wehlubal, Bundjalung

Eucalyptus Leaves

‘My brick features Eucalyptus leaves and gumnuts. I grew up a proud Aboriginal man however did not always know my mob. Not knowing my mob meant I never knew which Country I belonged to, and I always have struggled with being displaced from my culture. Despite this I used to find any way to connect to my culture and mob. I have always loved the bush, plants and animals, and would use my passion for these as a point of reference for my cultural identity. As gum trees are a widespread taxon of plants, I knew that also belonged to my Country. I would use gum trees as a symbol of my Blak identity and my fundamental connection to Country. I am a proud Kanolu and Gangulu Aboriginal Mari. I know my mob, I know my country sits in the North East of ‘Queensland’. I chose this item as it still represents who I am as an Aboriginal man, but also carries my story of reclaiming culture and Country. It may seem simple, but it is an item that connects me to my culture, ancestors and home.’

— Charlie Miller, Kanolu and Gangulu

Square Fur Armband

‘I am a 3rd Generation Stolen Generations child – I call us the Lost Generation. My nanna – Mum’s Mum – was taken as an infant from Toowoomba, Queensland and brought down to Victoria. Nan eventually found out she was Aboriginal and ended up living on the Cumeragunja Aboriginal Mission until she died. How she proved she was Aboriginal – so she could live on the mission – is information she did not share with the rest of the family. Mum and the family have been trying to figure out where we come from and who our Mob are. Her white name and her adoptive parent’s names are so varied that it is hard to prove any of them existed in the Western world. Birth certificates for Aboriginal children were often not made, so the only proof Nan existed at all is her grave and her children, and their children, and so on.

Growing up without the immersion of this culture and its customs has left a gap in our identity, so we have to fill that void in the closest ways possible. During my Undergrad at UoM I undertook a Summer Intensive class, led by the Wilin Centre: Ancient and Contemporary Indigenous Arts, hosted by our Dookie campus. We did many great activities such as experiencing the land, net making, help put together a possum-skin cloak, watch historic documentaries and listen to a local elder talk about how the Aboriginal populous of the area used to live. As a memento, we got to make a possum-skin armband with the scraps left from making the cloak. I chose 3 different skins of varying colour to sew together and braided the straps used to tie it to the arm. To me this is an expression of how we all look different, but we are all connected, and how as a people our skin may differ, but we are all the same on the inside (as the inside of the bands are all the same skin colour even though the fur differs). Cultural practices like these are important as, even though they may not be MY specific practices – whatever they may be – they are a link to my people, my heritage, my blood, my ancestral home.’

— Naome Cummins, Stolen Generation

Photograph of Siblings

‘This is one of few family photographs I own.

Captured on 35mm film back in the 1980s when Kodak was in business and photo processing required sending your film away, then an agonizing wait before you could see your snaps. Perpetually curious and eager to see the results of my photography endeavours, a week of waiting for me seemed an eternity. I have always loved taking photos - as a kid, I’d take my film to the chemist and wait until I could collect the prints. I was always chuffed on collection day.

Times have changed.

Those red-eyed, grainy textured, over-exposed vintage images, record my childhood: here is a photo of my brother Lindon and my sister Tameika. Mum isn’t in the picture, she’s in other ones.

There is no single photo where we are all together.

I think of the four of us as unique pieces of a puzzle. Unique, because we don’t quite know how we fit together. Our pieces don’t complete a picture on their own: in between us and before us, are those ‘invisible’ pieces, the ones we know are there but cannot see, the ones we cannot trace the edges to join us together, creating a large family picture. They are my ancestors, those my Mum longs to know and who we, her children do not know.

Here is the lens of our stolen generation.

It is very real.

It is tangible.

It is generational.

It is not a label.

This photo embraces people I love, people I have lost – and extends to all First Nation people in between.'

— Narida Yeatman-Morgan, Yorta Yorta

Kulaps

‘Kulaps is a shaker made from seeds tied together to make a rattling noise when shaken. The kulap is a dancing instrument used for traditional Torres Strait Islander dancing. It is made from Twine, and seeds from the matchbox bean. The dry seeds are cut in half, then strung onto twine to make the traditional musical instrument that is held by the dancers. The kulap compliments the island drum and singing during Torres Strait Islander dancers and ceremonies. These seeds have been collected from the rainforests and beaches throughout our Island waters.’

— John Wayne Parsons, Yuggerabul/ Narangawal/Gitabal man from southeast Queensland. Maluligal (Western Nation) and Kemer Kemer Meriam (Eastern Island Nation) of Torres Strait Islander

Emu Feather

‘The way to speak back to that tradition of colonial statues and memorials is to make our own.’

— Marcia Langton, Yiman and Bidjara

Sticks, Leaves and Feathers

‘I grew up in Canberra and am now living in Melbourne pursuing my dream by studying Acting at the Victorian college of the arts.

The Identity Bricks project was something that immediately sparked my interest but would eventually prove a bit overwhelming. It has taken me many years to come to terms with, research, and be proud of my First Nations identity. And so, finding a brick sized item that could represent my relationship to a culture I am still discovering became a bit intimidating.

It wasn’t until Melbourne’s 2021 lockdowns that I found something comforting. I can’t see any foliage or nature from the balcony of my claustrophobic student apartment, only grey concrete.

Eventually however, my balcony would gradually be littered with feathers, leaves, blades of grass and even a few petals. After months of my mental health decaying in isolation, I felt a bit safer and more in touch with the land. These random crumbs of foliage blown on to my balcony felt like nature checking up on me. It put me more in tune with the country to the point where more leaves blowing in felt like a gift from my country and Rain feels like a hug from mum.’

— Michael Cooper, (Grew up Ngunnawhal, mob is Awabakal/Worimi)

Small Rocks

‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identities are communal and place-based. The object(s) contained within this brick are a collection of stones and rocks from a freshwater creek, around 100~km outside of Cairns, Queensland. I have fond memories of my family, cousins, aunties and uncles at this creek growing up, swimming in the mountain cold water and jumping off the bridge. I even learnt to swim at this creek. I chose to include this collection because as a blakfulla who did not have the opportunity to grow up on Country, having pieces of ‘home’, away from home, allow me to connect with my identity off-Country. The physicality of the object also elicits a tangible feeling in my senses, from the fresh, clean, air of the Far North, the silent rumbling of cars passing by the highway, and the touch/feeling of these rocks below my feet.’

— Ethan Savage, Kaantju, Girramay, Badu Island

Paintbrush

'This paintbrush is a favourite of mine. Originally belonging to my father, he and I have both used it in the creation of countless artworks. For me it is an embodiment of the artistic practice which has kept me and my family rooted in place, Country and identity.'

— Tiriki Onus, Yorta Yorta and Dja Dja Wurrung

Dugong Bobbin

‘The object I selected for the project is a handcrafted Bobbin. This kind of bobbin would have originally been used to produced Dugong nets. I made this Bobbin using reference photos of two bobbins which belonged to my great great great grandfather, Sammy Roland. The original objects are now kept at The University of Queensland's Anthropology Museum. Sammy Roland would use the bobbins to produce Dugong nets, used to help catch Dugongs for ceremony and when rations were short, during the early 1900's while living on Myora Mission. My family still fish for our community today and although we use different nets, the knowledge of net making and repair is still very important and has been passed down throughout the community.’

— Ash Perry, Goenpul Quandamooka

Abalone Shells

‘Two abalone shells. One found by my father along the beach near home in lutruwita, and another found on Boon Wurrung Country, and gifted to me by Maree Clarke. They hold special significance to me.

I was born on Country in nipaluna, lutruwita, though for the most part of my life, I have grown-up off-Country. My family moved to Bundjalung Country when I was young. Since then, I have moved around a lot, and I now call Naarm home too.

Having grown-up in lutruwita, with a family who has lived and worked on or around the water for generations, abalone were always present. They are a reminder of family, of home, and the knowledge and memory embodied within and imparted by place.

Abalone are exploratory lifeforms that live in the littoral zone. Their shells grow as they do and embody a tightly wound spiral pattern that expands outward over time. As they move from place to place, their shells become layered with signs of life, movement, and survival – keeping them safe and connected to Country.

Here together, these two abalone shells acknowledge my ancestors, my family, and my friends who are family. They represent my journey, the lessons I have learnt along the way, the connections I have made, and the many places I call home. Held within and always carried with me.’

— Jessica Clark

Earth in Jar

‘I live and work on the lands of the Kulin nation but I have my country with me. Sandalwood from Badimia country and a piece of Warrdagga, our spiritual home.’

— Darren Clinch, Badimia Yamatji

Photograph

‘The item I have chosen to contribute to the ‘Identity Bricks Project’ is my first project I created which is centred around my Aboriginal heritage. The project itself is two small prints placed back to back of each other, three images on each side. Within the photographs is a young girl wearing various Indigenous jewellery.

Whilst selecting my item, it was important to choose an object that resonated with my culture and artistic practice.

This initial project was photographed in 2019, as I was interested in traditional jewellery and the process. Throughout this project I soon came to realise that I wanted the work to be humanised, which led me to ask my younger sister to model the jewellery. My Uncle Tiriki was incredibly generous to lend me the various jewellery I had photographed. Through this journey, I was able to understand my niche and my artistic views, which has led my practice to places unimaginable. This project assisted the connection to my heritage, as an artist I draw inspiration from my everyday life; thus creating the connection to my identity.’

— Mikaylah Lepua, Palawa

Identity Bricks Participant Videos

Some of the participants share their stories below.

Dugong Bobbin – Ash Perry, Goenpul Quandamooka Faculty of Fine Arts and Music

Painted Stethoscope – Cam Raw, Palawa Tutor in Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences

Manna Gum Leaves – Craig Hunter-Torrens, Wehlubal, Bundjalung Associate Lecturer

Yothu Yindi Cassette – Kirsten Hausia, Badimaya Yamatji Strategic Projects Coordinator

Sculpted Turtle and Emu Feather – Professor Marcia Langton, Yiman, Bidjara Professor & Associate Provost

Woven Earrings – Kayla Clinch, Badimaya Yamatji Project Officer & BA Student

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Indigenous staff, students and alumni who generously contributed a personal object to this project, this installation could not have been completed without your participation.

This appreciation is also extended to the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development, Murrup Barak Melbourne Institute for Indigenous Development, and Kane Constructions for their ongoing support of the Identity Bricks project.